The Thirty-Six Immortal Women Poets

The period of great innovation in Japanese calligraphy coincided with the flowering of court literature in the Late Heian period (897-1185). This period was notable for the prominence of the court women. Ladies’ poetry, diaries, and novels were characterized by wit and psychological insight. These women’s writings are now considered to be classics of world literature. The everyday Japanese language, Kana, was used by these women rather than the high court language. Kana (Japanese phonetic characters) provided women with a system of recording spoken language. It was often referred to as onna-de, literally translating as the “women’s hand.”

Both men and women at court were required to compose impromptu verses for all occasions. Kana calligraphy allowed for the advancement of waka (thirty-one-syllable court poetry) as well as other new forms of vernacular writing. It also played a crucial role in social interactions, including courtship rituals, since skills in calligraphy were thought to reflect a person’s overall sophistication. Courtiers were valued for the skill with which they inscribed official letters and court documents. An expert hand could help pave the way to a higher position. In high-society circles the ability to brush a poem or letter in flowing Kana became a skill that was expected.

In the eleventh century, Fujiwara Kinto (996-1075), a Japanese nobleman, scholar, and poet, selected thirty-six waka (36 syllable poems) by celebrated authors of the past; they came to be known as the Sanjurokkasen or Thirty-six Immortal Poets. Retired emperor Gotoba (1180-1239) early in the thirteenth century designated another group of poets, one hundred in all, as Immortal Poets. Based on these selections, painters produced albums and handscrolls featuring imaginary portraits of the poets together with samples of their verse. One of their favorite forms was to create imaginary poetry contests even though the dueling poets might have lived in different time periods.

The theme of the Thirty-six Immortal Poets has remained popular throughout Japanese history. The volumes produced showed the poets in Heian-era garb. The men were shown in stiff voluminous robes with wide-legged trousers (hakuma) and black lacquered caps (eboshi). Ladies wore sumptuous twelve-layer robes (junihitoe) with the colors and patterns of each layer visible at the sleeves and hems.

Beginning in the tenth century, poetry contests (uta-awase) were a favorite pastime of the Japanese court. Teams would be divided into left and right, and poems were often recorded for posterity in elegant calligraphy. Imaginary poetry contests that pitted esteemed poets of the past against each other were often accompanied by stylized portraits of the participants.

Calligraphers of such poetry-contest handscrolls frequently employed “scattered writing” (chirashigaki), used to describe two related types of calligraphic devices; phrases of a poem inscribed in normal sequence, but with columns or characters divided and spaced in a seemingly random arrangement on the page; or lines and words of a poem (usually a well-known one) arranged out of normal syntax. The primary motive of chirashigaki is to create an interesting arrangement of ink lines and blank spaces, yet it often had the secondary effect of imposing a new rhythm of reading. Words divided artificially, lines broken at the wrong places, columns overlapped to create entangled phrases – all result in a slightly slower reading process. The eye must linger a bit, perhaps go back and forth, to understand the message.

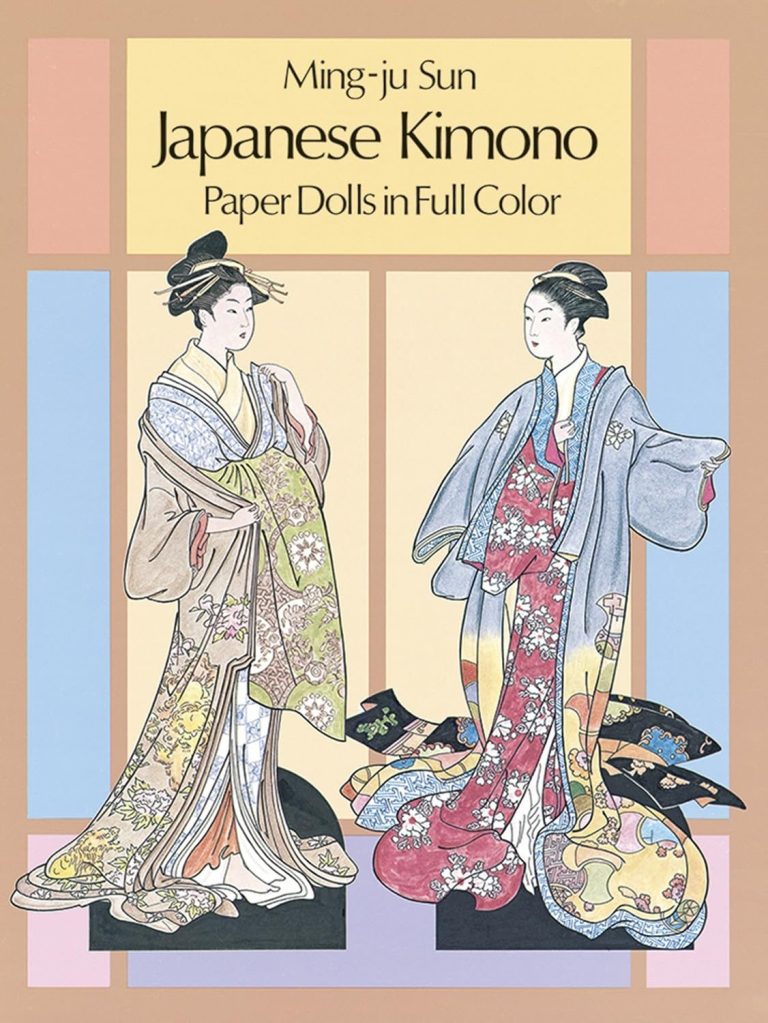

I became interested in Japanese design when I was at Georgia State University completing my MFA. My Masters Thesis concerned the universal use of patterning and order as an elements in art. About 12 years ago I found a copy of the Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets at a used book sale. I was interested in the book because it was designed beautifully, it had a unique order and system, and was about girls and women. For twelve years I knew I would use it for collage. In Seattle on vacation in 2013 we visited the Asian Museum and I found the paper dolls. Upon arriving home I immediately started putting the different elements together for these images. Each piece has a poet with her poem in English, Japanese, and calligraphy, a paper doll, and a representation of a kimono. My goal was to use this information in a new way that would help preserve and bring to people’s attention the wonderful cultural heritage of Japanese women.

Ming-ju Sun designed the Japanese Kimono paper dolls. She was inspired by the 18th and 19th-century Japanese woodblock prints of the school of ukiyo-e “pictures of the floating world”. She looked at such artists as Utamaro, Hiroshige, Eizen, Harunobu and Eishi.

The book The Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets reproduces a woodblock printed album in the Spencer Collection of the New York Library. The original album was published by Ejudo Nishimuraya Yohachi in Edo (Tokyo) in 1801 as a deluxe album of thirty-six color prints. Each double page shows a poet on the left and one of her poems on the right in calligraphy. There is a frontispiece by Hokusai, a preface in Japanese (missing from the Spencer Collection), afterwords in Chinese, one in Japanese and finally a colophon (also missing in this album. The illustrations of the poets were designed by Hosoda (Chobunsai) Eishi (1756-1829) and the poems were written in calligraphy in 1797 by thirty-six girls between the ages of six and fifteen.

The album originally functioned as a publicity vehicle to show the accomplishments of the young girls, whose calligraphy records the poems. On the right-hand margin of the calligraphy is a small note recording the address, name and age of the child responsible. 5 LEFT and 6 LEFT were brushed by two sisters, ages 6 and 10. The girls were all students of Hanagata Yoshiakira who presided over the Hanagata Shodo (a calligraphy school.) The school sponsored the publication of the album probably to solicit new students or to serve as a model book. According to an advertisement that accompanies the colophon, a complimentary illustrated text of Thirty-six poets by male students was also planned. This album was never published.

The album works well as an advertisement; the calligraphy looks professional and uniform. This may be due to the models that the children were copying or the skill of the woodblock carvers (recorded in the colophon as Yamaguchi Matsugro and Yamaguchi Kiyozo.) To demonstrate the training these young girls had received their calligraphy went beyond the simple skill of drawing kana (the elements of Japanese syllabic script); they transcribed the poems in many formats. They varied from regular even lines to complex scatterings of syllables that almost require a map to read. The variety showed that the girls were learning to write with surprising facility and were learning the aesthetics of calligraphy and the fundamental principles of poetry. This would be compelling to affluent parents who wanted to see their children introduced to the world of classical Japanese culture.

These poets and poems were already part of Japan’s distant past. Over five hundred years separated the time of the latest poet in the collection from the time when the girls were writing. At the time, the style of dress was only worn by a few nobles in Kyoto for ceremonial occasions.

When this album was published it was an affordable version of the richly painted scrolls and albums from the golden age of court society. The poets in this album were active during Heian (794-1185) and Kamakura (1185-1333) periods, from the ninth century through the mid-thirteenth century. During this time the imperial court in Kyoto was the center of an extraordinarily sophisticated culture that held poetry in the highest regard as well as calligraphy, dance, music, and painting. Knowledge of the classics began to spread more widely in the seventeenth century when printed versions of the anthologies were produced. Before they were printed, the descendants of the old aristocratic families preserved them.

The information in this preface has been taken from the Metropolitan Museum’s website (met.org), The Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets and Japanese Kimono Paper dolls.

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.